Intermediate Accountingch answerch11

CHAPTER 11

Depreciation, Impairments, and Depletion ASSIGNMENT CLASSIFICATION TABLE (BY TOPIC)

Topics Questions

Brief

Exercises Exercises Problems

Concepts

for Analysis

1. Depreciation methods;

meaning of depreciation;

choice of depreciation

methods. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

6, 10, 14,

20, 21, 22

1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

8, 14, 15

1, 2, 3 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

2. Computation of

depreciation. 7, 8, 9, 13 1, 2, 3, 4 1, 2, 3, 4,

5, 6, 7,

10, 15

1, 2, 3,

4, 8, 10,

11, 12

1, 2, 3

3. Depreciation base. 6, 7 5 8, 14 1, 2, 3,

8, 10

3

4. Errors; changes in

estimate. 13 7 11, 12,

13, 14

3, 4 3

5. Depreciation of partial

periods. 15 2, 3, 4 3, 4, 5, 6,

7, 15

1, 2, 3,

10, 11

6. Composite method. 11, 12 6 9 2

7. Impairment of value. 16, 17, 18,

19, 29, 30,

31, 32

8 16, 17, 18 9

8. Depletion. 22, 23, 24,

25, 26, 27 9 19, 20, 21,

22, 23

5, 6, 7

9. Ratio analysis. 28 10 24

*10. Tax depreciation

(MACRS).

33 11 25, 26 12 *This material is covered in an Appendix to the chapter.

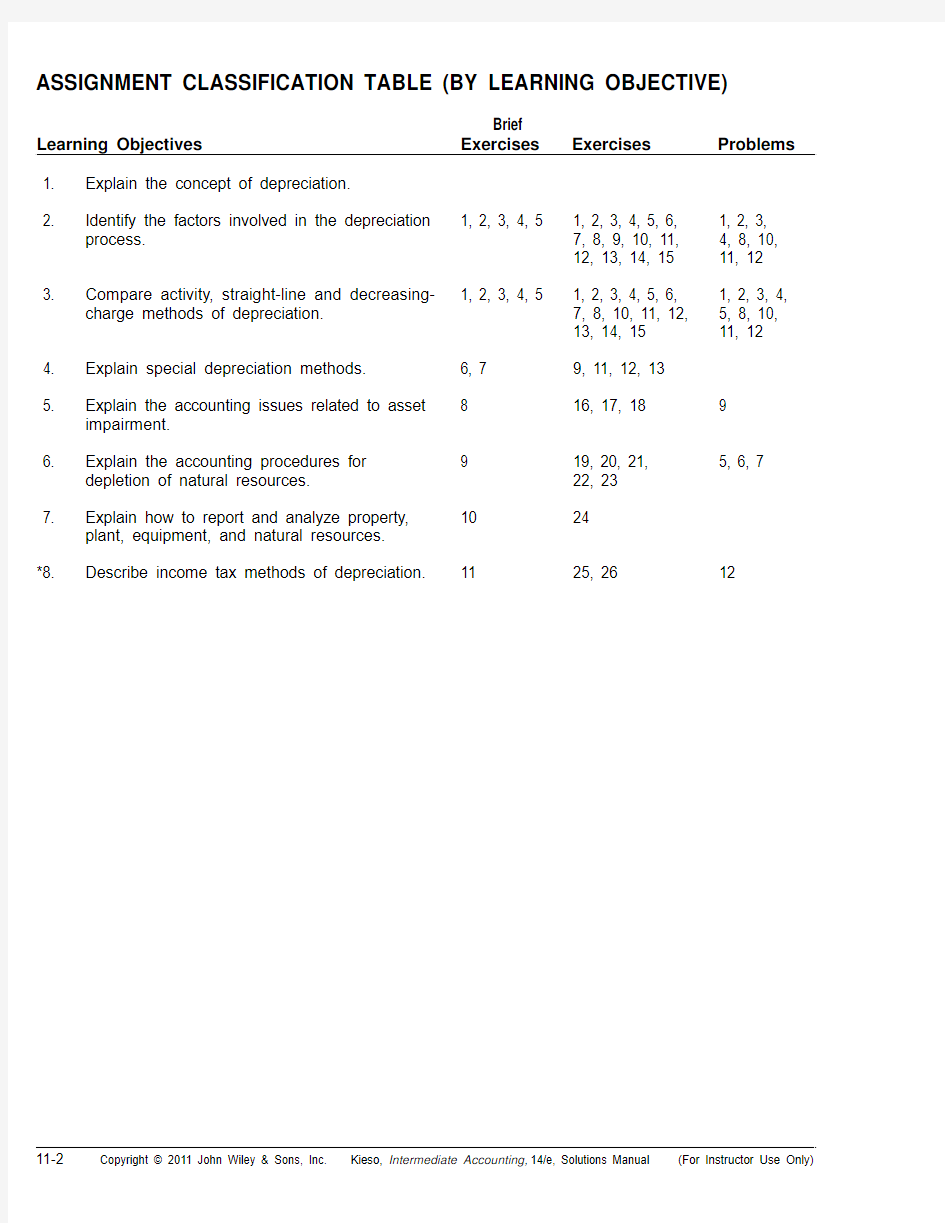

ASSIGNMENT CLASSIFICATION TABLE (BY LEARNING OBJECTIVE)

Learning Objectives Brief

Exercises Exercises Problems

1. Explain the concept of depreciation.

2. Identify the factors involved in the depreciation

process. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6,

7, 8, 9, 10, 11,

12, 13, 14, 15

1, 2, 3,

4, 8, 10,

11, 12

3. Compare activity, straight-line and decreasing-

charge methods of depreciation. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6,

7, 8, 10, 11, 12,

13, 14, 15

1, 2, 3, 4,

5, 8, 10,

11, 12

4. Explain special depreciation methods. 6, 7 9, 11, 12, 13

5. Explain the accounting issues related to asset

impairment.

8 16, 17, 18 9

6. Explain the accounting procedures for

depletion of natural resources. 9 19, 20, 21,

22, 23

5, 6, 7

7. Explain how to report and analyze property,

plant, equipment, and natural resources.

10 24

*8. Describe income tax methods of depreciation. 11 25, 26 12

ASSIGNMENT CHARACTERISTICS TABLE

Item Description Level of

Difficulty

Time

(minutes)

E11-1 Depreciation computations—SL, SYD, DDB. Simple 15–20 E11-2 Depreciation—conceptual understanding. Moderate 20–25 E11-3 Depreciation computations—SYD, DDB—partial periods. Simple 15–20 E11-4 Depreciation computations—five methods. Simple 15–25 E11-5 Depreciation computations—four methods. Simple 20–25 E11-6 Depreciation computations—five methods, partial periods. Moderate 20–30 E11-7 Different methods of depreciation. Simple 25–35 E11-8 Depreciation computation—replacement, nonmonetary

exchange.

Moderate 20–25 E11-9 Composite depreciation. Simple 15–20 E11-10 Depreciation computations, SYD. Simple 10–15 E11-11 Depreciation—change in estimate. Simple 10–15 E11-12 Depreciation computation—addition, change in estimate. Simple 20–25 E11-13 Depreciation—replacement, change in estimate. Simple 15–20 E11-14 Error analysis and depreciation, SL and SYD. Moderate 20–25 E11-15 Depreciation for fractional periods. Moderate 25–35 E11-16 Impairment. Simple 10–15 E11-17 Impairment. Simple 15–20 E11-18 Impairment. Simple 15–20 E11-19 Depletion computations—timber. Simple 15–20 E11-20 Depletion computations—oil. Simple 10–15 E11-21 Depletion computations—timber. Simple 15–20 E11-22 Depletion computations—mining. Simple 15–20 E11-23 Depletion computations—minerals. Simple 15–20 E11-24 Ratio analysis. Moderate 15–20 *E11-25 Book vs. tax (MACRS) depreciation. Moderate 20–25 *E11-26 Book vs. tax (MACRS) depreciation. Moderate 15–20 P11-1 Depreciation for partial period—SL, SYD, and DDB. Simple 25–30 P11-2 Depreciation for partial periods—SL, Act., SYD, and DDB. Simple 25–35 P11-3 Depreciation—SYD, Act., SL, and DDB. Moderate 40–50 P11-4 Depreciation and error analysis. Complex 45–60 P11-5 Depletion and depreciation—mining. Moderate 25–30 P11-6 Depletion, timber, and extraordinary loss. Moderate 25–30 P11-7 Natural resources—timber. Moderate 25–35 P11-8 Comprehensive fixed asset problem. Moderate 25–35 P11-9 Impairment. Moderate 15–25 P11-10 Comprehensive depreciation computations. Complex 45–60

ASSIGNMENT CHARACTERISTICS TABLE (Continued)

Item Description Level of

Difficulty

Time

(minutes)

P11-11 Depreciation for partial periods—SL, Act., SYD,

and DDB.

Moderate 30–35 *P11-12 Depreciation—SL, DDB, SYD, Act., and MACRS. Moderate 25–35 CA11-1 Depreciation basic concepts. Moderate 25–35 CA11-2 Unit, group, and composite depreciation. Simple 20–25 CA11-3 Depreciation—strike, units-of-production, obsolescence. Moderate 25–35 CA11-4 Depreciation concepts. Moderate 25–35 CA11-5 Depreciation choice—ethics. Moderate 20–25

SOLUTIONS TO CODIFICATION EXERCISES

CE11-1

(a) The master glossary provides two entries for amortization:

Amortization

The process of reducing a recognized liability systematically by recognizing revenues or reducing

a recognized asset systematically by recognizing expenses or costs. In pension accounting,

amortization is also used to refer to the systematic recognition in net pension cost over several periods of amounts previously recognized in other comprehensive income, that is, prior service costs or credits, gains or losses, and the transition asset or obligation existing at the date of initial application of Subtopic 715-30.

Amortization

The process of reducing a recognized liability systematically by recognizing revenues or by reducing a recognized asset systematically by recognizing expenses or costs. In accounting for postretirement benefits, amortization also means the systematic recognition in net periodic postre-tirement benefit cost over several periods of amounts previously recognized in other comprehen-sive income, that is, gains or losses, prior service cost or credits, and any transition obligation or asset.

(b) Impairment is the condition that exists when the carrying amount of a long-lived asset (asset

group) exceeds its fair value.

(c) Recoverable amount is the current worth of the net amount of cash expected to be recoverable

from the use or sale of an asset.

(d) According to the glossary, the term activities is to be construed broadly. It encompasses physical

construction of the asset. In addition, it includes all the steps required to prepare the asset for its intended use. For example, it includes administrative and technical activities during the precon-struction stage, such as the development of plans or the process of obtaining permits from governmental authorities. It also includes activities undertaken after construction has begun in order to overcome unforeseen obstacles, such as technical problems, labor disputes, or litigation. CE11-2

According to FASB ASC 360-10-40-4 through 6 (Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets . . . Long-Lived Assets to Be Exchanged or to Be Distributed to Owners in a Spinoff):

40-4For purposes of this Subtopic, a long-lived asset to be disposed of in an exchange measured based on the recorded amount of the nonmonetary asset relinquished or to be distributed to owners in a spinoff is disposed of when it is exchanged or distributed. If the asset (asset group) is tested for recoverability while it is classified as held and used, the estimated future cash flows used in that test shall be based on the use of the asset for its remaining useful life, assuming that the disposal transaction will not occur. In such a case, an undiscounted cash flows recoverability test shall apply prior to the disposal date. In addition to any impairment losses required to be recognized while the asset is classified as held and used, and impairment loss, if any, shall be recognized when the asset is disposed of if the carrying amount of the asset (disposal group) exceeds its fair value. The provisions of this Section apply to nonmonetary exchanges that are not recorded at fair value under the provisions of Topic 845.

CE11-2 (Continued)

40-5 A gain or loss not previously recognized that results from the sale of a long-lived asset (disposal group) shall be recognized at the date of sale.

40-6 See paragraphs 360-10-35-47 through 35-48 for guidance related to the disposition of an asset upon its abandonment.

CE11-3

According to FASB ASC 360-10-35-1 through 10 (Subsequent Measurement):

35-1 This Subsection addresses property, plant, and equipment, subsequent measurement issues related to depreciation and the acquisition of an interest in the residual value of a leased asset.

35-2 This guidance addresses the concept of depreciation accounting and the various factors to consider in selecting the related periods and methods to be used in such accounting.

35-3 Depreciation expense in financial statements for an asset shall be determined based on the asset’s useful life.

35-4The cost of a productive facility is one of the costs of the services it renders during its useful economic life. Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) require that this cost be spread over the expected useful life of the facility in such a way as to allocate it as equitably as possible to the periods during which services are obtained from the use of the facility. This procedure is known as depreciation accounting, a system of accounting which aims to distribute the cost or other basic value of tangible capital assets, less salvage (if any), over the estimated useful life of the unit (which may be a group of assets) in a systematic and rational manner. It is a process of allocation, not of valuation.

35-5See paragraph 360-10-35-20 for a discussion of depreciation of a new cost basis after recognition of an impairment loss.

35-6See paragraph 360-10-35-43 for a discussion of cessation of deprecation on long-lived assets classified as held for sale.

35-7The declining-balance method is an example of one of the methods that meet the requirements of being systematic and rational. If the expected productivity or revenue-earning power of the asset is relatively greater during the earlier years of its life, or maintenance charges tend to increase during later years, the declining-balance method may provide the most satisfactory allocation of cost. That conclusion also applies to other methods, including the sum-of-the-years’-digits method, that produce substantially similar results.

55-8In practice, experience regarding loss or damage to depreciable assets is in some cases one of the factors considered in estimating the depreciable lives of a group of depreciable assets, along with such other factors as wear and tear, obsolescence, and maintenance and replacement policies. 35-9 If the number of years specified by the Accelerated Cost Recovery System of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for recovery deductions for an asset does not fall within a reasonable range of the asset’s useful life, the recovery deductions shall not be used as depreciation expense for financial reporting.

35-10Annuity methods of depreciation are not acceptable for entities in general.

CE11-4

According to FASB ASC 210-10-S99 (Balance Sheet-Overall-SEC Materials)

SEC Rules, Regulations, and Interpretations

>> Regulation S-X

>>> Regulations, S-X Rule 5-02, Balance Sheets

S99-1The following is the text of Regulation S-X Rule 5-02, Balance Sheets.

The purpose of this rule is to indicate the various line items and certain additional disclosures which, if applicable, and except as otherwise permitted by the Commission, should appear on the face of the balance sheets or related notes filed for the persons to whom this article pertains (see § 210.4–01(a)).

Assets And Other Debits

13. Property, plant and equipment.

–(a) State the basis of determining the amount.

–(b) Tangible and intangible utility plant of a public utility company shall be segregated so as to show separately the original cost, plant acquisition adjustments, and

plant adjustments, as required by the system of accounts prescribed by the

applicable regulatory authorities. This rule shall not be applicable in respect to

companies which are not required to make much a classification.

14. Accumulated depreciation, depletion, and amortization of property, plant and equipment.

The amount is to be set forth separately in the balance sheet or in a note thereto.

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS

1.The differences among the terms depreciation, depletion, and amortization are that they imply a

cost allocation of different types of assets. Depreciation is employed to indicate that tangible plant assets have decreased in carrying value. Where natural resources (wasting assets) such as timber, oil, coal, and lead are involved, the term depletion is used. The expiration of intangible assets such as patents or copyrights is referred to as amortization.

2. The factors relevant in determining the annual depreciation for a depreciable asset are the initial

recorded amount (cost), estimated salvage value, estimated useful life, and depreciation method.

Assets are typically recorded at their acquisition cost, which is in most cases objectively determinable.

But cost assignment in other cases—―basket purchases‖ and the selection of an implicit interest rate in asset acquisitions under deferred-payment plans—may be quite subjective, involving considerable judgment.

The salvage value is an estimate of an amount potentially realizable when the asset is retired from service. The estimate is based on judgment and is affected by the length of the useful life of the asset.

The useful life is also based on judgment. It involves selecting the ―unit‖ of m easure of service life and estimating the number of such units embodied in the asset. Such units may be measured in terms of time periods or in terms of activity (for example, years or machine hours). When selecting the life, one should select the lower (shorter) of the physical life or the economic life. Physical life involves wear and tear and casualties; economic life involves such things as technological obsolescence and inadequacy.

Selecting the depreciation method is generally a judgment decision, but a method may be inherent in the definition adopted for the units of service life, as discussed earlier. For example, if such units are machine hours, the method is a function of the number of machine hours used during each period. A method should be selected that will best measure the portion of services expiring each period. Once a method is selected, it may be objectively applied by using a predetermined, objec-tively derived formula.

3.Disagree. Accounting depreciation is defined as an accounting process of allocating the costs of

tangible assets to expense in a systematic and rational manner to the periods expected to benefit from the use of the asset. Thus, depreciation is not a matter of valuation but a means of cost allocation.

4.The carrying value of a fixed asset is its cost less accumulated depreciation. If the company estimates

that the asset will have an unrealistically long life, periodic depreciation charges, and hence accumulated depreciation, will be lower. As a result the carrying value of the asset will be higher. 5. A change in the amount of annual depreciation recorded does not change the facts about the decline

in economic usefulness. It merely changes reported figures. Depreciation in accounting consists of allocating the cost of an asset over its useful life in a systematic and rational manner. Abnormal obsolescence, as suggested by the plant manager, would justify more rapid depreciation, but increasing the depreciation charge would not necessarily result in funds for replacement. It would not increase revenue but simply make reported income lower than it would have been, thus preventing overstatement of net income.

Recording depreciation on the books does not set aside any assets for eventual replacement of the depreciated assets. Fund segregation can be accomplished but it requires additional managerial action. Unless an increase in depreciation is accompanied by an increase in sales price of the product, or unless it affects management’s decision on dividend policy, it does not affect funds.

Questions Chapter 11 (Continued)

Ordinarily higher depreciation will not lead to higher sales prices and thus to more rapid ―recovery‖ of the cost of the asset, and the economic factors present would have permitted this higher price regardless of the excuse given or the particular rationalization used. The price could have been increased without a higher depreciation charge.

The funds of a firm operating profitably do increase, but these may be used as working capital policy may dictate. The measure of the increase in these funds from operations is not merely net income, but that figure plus charges to operations which did not require working capital, less credits to operations which did not create working capital. The fact that net income alone does not measure the increase in funds from profitable operations leads some non-accountants to the erroneous conclusion that a fund is being created and that the amount of depreciation recorded affects the fund accumulation.

Acceleration of depreciation for purposes of income tax calculation stands in a slightly different category, since this is not merely a matter of recordkeeping. Increased depreciation will tend to postpone tax payments, and thus temporarily increase funds (although the liability for taxes may be the same or even greater in the long run than it would have been) and generate gain to the firm to the extent of the value of use of the extra funds.

6.Assets are retired for one of two reasons: physical factors or economic factors—or a combination

of both. Physical factors are the wear and tear, decay, and casualty factors which hinder the asset from performing indefinitely. Economic factors can be interpreted to mean any other constraint that develops to hinder the service life of an asset. Some accountants attempt to classify the economic factors into three groups: inadequacy,supersession, and obsolescence. Inadequacy is defined as a situation where an asset is no longer useful to a given enterprise because the demands of the firm have increased. Supersession is defined as a situation where the replacement of an asset occurs because another asset is more efficient and economical. Obsolescence is the catchall term that encompasses all other situations and is sometimes referred to as the major concept when economic factors are considered.

7.Before the amount of the depreciation charge can be computed, three basic questions must be

answered:

(1) What is the depreciation base to be used for the asset?

(2) What is the asset’s useful life?

(3) What method of cost apportionment is best for this asset?

8. Cost $800,000 Cost $800,000

Depreciation rate X 30%* Depreciation for 2012 (240,000) Depreciation for 2012 $240,000 Undepreciated cost in 2013 560,000

Depreciation rate X 30% 2012 Depreciation $240,000 Depreciation for 2013 $168,000 2013 Depreciation 168,000

Accumulated depreciation

at December 31, 2013 $408,000

*(1 ÷ 5) X 150%

Questions Chapter 11 (Continued)

9. Depreciation base:

Cost $162,000 Straight-line, $147,000 ÷ 20 = $ 7,350 Salvage (15,000)

$147,000 Units-of-output, $147,000

X 20,000 = $35,000

84,000

Working hours, $147,000

X 14,300 = $50,050

42,000

Sum-of-the-years’-digits, $147,000 X 20/210* = $14,000

Double-declining-balance, $162,000 X 10% = $16,200

*20(20+1)

=210

2

10.From a conceptual point of view, the method which best matches revenue and expenses should

be used; in other words, the answer depends on the decline in the service potential of the asset. If the service potential decline is faster in the earlier years, an accelerated method would seem to be more desirable. On the other hand, if the decline is more uniform, perhaps a straight-line approach should be used. Many firms adopt depreciation methods for more pragmatic reasons. Some companies use accelerated methods for tax purposes but straight-line for book purposes because

a higher net income figure is shown on the books in the earlier years, but a lower tax is paid to the

government. Others attempt to use the same method for tax and accounting purposes because it eliminates some recordkeeping costs. Tax policy sometimes also plays a role.

11.The composite method is appropriate for a company which owns a large number of heterogeneous

plant assets and which would find it impractical to keep detailed records for them.

The principal advantage is that it is not necessary to keep detailed records for each plant asset in the group. The principal disadvantage is that after a period of time the book value of the plant assets may not reflect the proper carrying value of the assets. Inasmuch as the Accumulated Depreciation account is debited or credited for the difference between the cost of the asset and the cash received from the retirement of the asset (i.e., no gain or loss on disposal is recognized), the Accumulated Depreciation account is self-correcting over time.

12.Cash ................................................................................................... 14,000

Accumulated Depreciation—Plant Assets ........................................... 36,000

Plant Assets ....................................................................... 50,000 No gain or loss is recognized under the composite method.

13.Original estimate: $2,500,000 ÷ 50 = $50,000 per year

Depreciation to January 1, 2013: $50,000 X 24 = $1,200,000

Depreciation in 2013 ($2,500,000 – $1,200,000) ÷ 15 years = $86,667

14.No, depreciation does not provide cash; revenues do. The funds for the replacement of the assets

come from the revenues; without the revenues no income materializes and no cash inflow results.

A separate decision must be made by management to set aside cash to accumulate asset replace-

ment funds. Depreciation is added to net income on the statement of cash flows (indirect method) because it is a noncash expense, not because it is a cash inflow.

Questions Chapter 11 (Continued)

15.25% straight-line rate X 2 = 50% double-declining rate

$8,000 X 50% = $4,000 Depreciation for first full year.

$4,000 X 6/12 = $2,000 Depreciation for half a year (first year), 2012.

$6,000 X 50% = $3,000 Depreciation for 2013.

16.The accounting standards require that if events or changes in circumstances indicate that the

carrying amount of such assets may not be recoverable, then the carrying amount of the asset should be assessed. The assessment or review takes the form of a recoverability test that compares the sum of the expected future cash flows from the asset (undiscounted) to the carrying amount. If the cash flows are less than the carrying amount, the asset has been impaired. The impairment loss is measured as the amount by which the carrying amount exceeds the fair value of the asset. The fair value of assets is measured by their market value if an active market for them exists. If no market price is available, the present value of the expected future net cash flows from the asset may be used.

17.Under U.S. GAAP, impairment losses on assets held for use may not be restored.

18.An impairment is deemed to have occurred if, in applying the recoverability test, the carrying

amount of the asset exceeds the expected future net cash flows from the asset. In this case, the expected future net cash flows of $705,000 exceed the carrying amount of the equipment of $700,000 so no impairment is assumed to have occurred; thus no measurement of the loss is made or recognized even though the fair value is $590,000.

19. Impairment los ses are reported as part of income from continuing operations, generally in the ―Other

expenses and losses‖ section. Impairment losses (and recovery of losses for assets to be disposed of) are similar to other costs that would flow through operations. Thus, gains (recoveries of losses) on assets to be disposed of should be reported as part of income from continuing operations in the ―Other revenues and gains‖ section.

20. In a decision to replace or not to replace an asset, the undepreciated cost of the old asset is not a

factor to be considered. Therefore, the decision to replace plant assets should not be affected by the amount of depreciation that has been recorded. The relative efficiency of new equipment as compared with that presently in use, the cost of the new facilities, the availability of capital for the new asset, etc., are the factors entering into the decision. Normally, the fact that the asset had been fully depreciated through the use of some accelerated depreciation method, although the asset was still in use, should not cause management to decide to replace the asset. If the new asset under consideration for replacement was not any more efficient than the old, or if it cost a good deal more in relationship to its efficiency, it is illogical for management to replace it merely because all or the major portion of the cost had been charged off for tax and accounting purposes.

If depreciation rates were higher it might be true that a business would be financially more able to replace assets, sin ce during the earlier years of the asset’s use a larger portion of its cost would have been charged to expense, and hence during this period a smaller amount of income tax paid.

By selling the old asset, which might result in a capital gain, and purchasing a new asset, the higher depreciation charge might be continued for tax purposes. However, if the asset were traded in, having taken higher depreciation would result in a lower basis for the new asset.

It should be noted that expansion (not merely replacement) might be encouraged by increased depreciation rates. Management might be encouraged to expand, believing that in the first few years when they are reasonably sure that the expanded facilities will be profitable, they can charge off a substantial portion of the cost as depreciation for tax purposes. Similarly, since a replacement involves additional capital outlays, the tax treatment may have some influence.

Also, because of the inducement to expand or to start new businesses, there may be a tendency in the economy as a whole for the accounting and tax treatment of the cost of plant assets to influence the retirement of old plant assets.

Questions Chapter 11 (Continued)

It should be noted that to the extent that increased depreciation causes management to alter its decision about replacement, and to the extent it results in capital gains at the time of disposition, it is not matching costs and revenues in the closest possible manner.

21.In lieu of recording depreciation on replacement costs, management might elect to make annual

appropriations of retained earnings in contemplation of replacing certain facilities at higher price levels. Such appropriations might help to eliminate misunderstandings as to amounts available for distribution as dividends, higher wages, bonuses, or lower sales prices. The need for these appropriations can be explained by supplementary financial schedules, explanations, and footnotes accompanying the financial statements. (However, neither depreciation charges nor appropriations of retained earnings result in the accumulation of funds for asset replacement. Fund accumulation is a result of profitable operations and appropriate funds management.)

22.(a) Depreciation and cost depletion are similar in the accounting sense in that:

1. The cost of the asset is the starting point from which computation of the amount of the

periodic charge to operations is made.

2. The estimated life is based on economic or productive life.

3. The accumulated total of past charges to operations is deducted from the original cost of

the asset on the balance sheet.

4. When output methods of computing depreciation charges are used, the formulas are

essentially the same as those used in computing depletion charges.

5. Both represent an apportionment of cost under the process of matching costs with revenue.

6. Assets subject to either are reported in the same classification on the balance sheet.

7. Appraisal values are sometimes used for depreciation while discovery values are sometimes

used for depletion.

8. Residual value is properly recognized in computing the charge to operations.

9. They may be included in inventory if the related asset contributed to the production of the

inventory.

10. The rates may be changed upon revision of the estimated productive life used in the

original rate computations.

(b) Depreciation and cost depletion are dissimilar in the accounting sense in that:

1. Depletion is almost always based on output whereas depreciation is usually based on time.

2. Many formulas are used in computing depreciation but only one is used to any extent in

computing depletion.

3. Depletion applies to natural resources while depreciation applies to plant and equipment.

4. Depletion refers to the physical exhaustion or consumption of the asset while depreciation

refers to the wear, tear, and obsolescence of the asset.

5. Under statutes which base the legality of dividends on accumulated earnings, depreciation

is usually a required deduction but depletion is usually not a required deduction.

6. The computation of the depletion rate is usually much less precise than the computation of

depreciation rates because of the greater uncertainty in estimating the productive life.

7. A difference that is temporary in nature arises from the timing of the recognition of

depreciation under conventional accounting and under the Internal Revenue Code, and it

results in the recording of deferred income taxes. On the other hand, the difference

between cost depletion under conventional accounting and its counterpart, percentage

depletion, under the Internal Revenue Code is permanent and does not require the

recording of deferred income taxes.

23.Cost depletion is the procedure by which the capitalized costs, less residual land values, of a natural

resource are systematically charged to operations. The purpose of this procedure is to match the cost of the resource with the revenue it generates. The usual method is to divide the total cost less residual value by the estimated number of recoverable units to arrive at a depletion charge for each unit removed. A change in the estimate of recoverable units will necessitate a revision of the unit charge.

Questions Chapter 11 (Continued)

Percentage depletion is the procedure, authorized by the Internal Revenue Code, by which a certain percentage of gross income is charged to operations in arriving at taxable income. Percentage depletion is not considered to be a generally accepted accounting principle because it is not related to the cost of the asset and is allowed even though the property is fully depleted under cost depletion accounting. Applicable rates, ranging from 5% to 22% of gross income, are specified for nearly all natural resources. The total amount deductible in a given year may not be less than the amount computed under cost depletion procedures, and it may not exceed 50% of taxable income from the property before the depletion deduction. Cost depletion differs from percentage depletion in that cost depletion is a function of production whereas percentage depletion is a function of income.

Percentage depletion has arisen, in part, from the difficulty of valuing the natural resource or determining the discovery value of the asset and of determining the recoverable units. Although other arguments have been advanced for maintaining percentage depletion, a primary argument is its value in encouraging the search for additional resources. It is deemed to be in the national interest to provide an incentive to the continuing search for natural resources. As noted in the textbook, percentage depletion is no longer permitted for many enterprises.

24.Percentage depletion does not necessarily measure the proper share of the cost of land to be charged

to expense for depletion and, in fact, may ultimately exceed the actual cost of the property.

25.The maximum dividend permissible is the amount of accumulated net income (after depletion) plus

the amount of depletion charged. This practice can be justified for companies that expect to extract natural resources and not purchase additional properties. In effect, such companies are distributing gradually to stockholders their original investments.

26.Reserve recognition accounting (RRA) is the method that was proposed by the SEC to account for

oil and gas resources. Proponents of this approach argue that oil and gas should be valued at the date of discovery. The value of the reserve still in the ground is estimated and this amount, appropriately discounted, is reported on the balance sheet as ―oil deposits.‖

The costs of exploration incurred each year are deducted from the estimated reserves discovered during the same period with the difference probably being reported as income.

The oil companies are concerned because the valuation issue is extremely tenuous. For example, to properly value the reserves, the following must be estimated: (1) amount of the reserves, (2) future production costs, (3) periods of expected disposal, (4) discount rate, and (5) the selling price.

27. Using full-cost accounting, the cost of unsuccessful ventures as well as those that are successful is

capitalized, because a cost of drilling a dry hole is a cost that is needed to find the commercially profitable wells. Successful efforts accounting capitalizes only those costs related to successful projects. They contend that to measure cost and effort accurately for a single property unit, the only measure is in terms of the cost directly related to that unit. In addition, it is argued that full-cost is misleading because capitalizing all costs will make an unsuccessful company over a short period of time show no less income than does one that is successful.

28.Asset turnover ratio:

$63.4 = 1.4 times

Rate of return on assets:

$2.5 = 5.6%

$44.3

Questions Chapter 11 (Continued)

*29. The modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS) has been adopted by the Internal Revenue Service. It applies to depreciable assets acquired in 1987 and later. MACRS eliminates the need to determine each asset’s useful life. The selection of a depreciation method a nd a salvage

value is also unnecessary under MACRS. The taxpayer determines the recovery deduction for an asset by applying a statutory percentage to the historical cost of the property. MACRS was adopted to permit a faster write-off of tangible assets so as to provide additional tax incentives and to simplify the depreciation process. The simplification should end disputes related to estimated useful life, salvage value, and so on.

SOLUTIONS TO BRIEF EXERCISES BRIEF EXERCISE 11-1

2012: ($50,000 – $2,000) X 23,000 = $6,900

160,000

2013: ($50,000 – $2,000) X 31,000 = $9,300

160,000

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-2

(a) $80,000 – $8,000 = $9,000

8

(b) $80,000 – $8,000 X 4/12 = $3,000 8

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-3

(a) ($80,000 – $8,000) X 8/36* = $16,000

(b) [($80,000 – $8,000) X 8/36] X 9/12 = $12,000

*[8(8 + 1)] ÷ 2

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-4

(a) $80,000 X 25%* = $20,000

(b) ($80,000 X 25%) X 3/12 = $5,000

*(1/8 X 2)

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-5

Depreciable Base = ($28,000 + $200 + $125 + $500 + $475) – $3,000 = $26,300.

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-6

Asset Depreciation Expense

A ($70,000 – $7,000)/10 = $ 6,300

B ($50,000 – $5,000)/5 = 9,000

C ($82,000 – $4,000)/12 = 6,500

$21,800

Composite rate = $21,800/$202,000 = 10.8%

Composite life = $186,000*/$21,800 = 8.5 years

*($63,000 + $45,000 + $78,000)

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-7

Annual depreciation expense: ($8,000 – $1,000)/5 = $1,400

Book value, 1/1/13: $8,000 – (2 x $1,400) = $5,200

Depreciation expense, 2013: ($5,200 – $500)/2 = $2,350

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-8

Recoverability test:

Future net cash flows ($500,000) < Carrying amount ($520,000);

therefore, the asset has been impaired.

Journal entry:

Loss on Impairment ..................................................120,000

Accumulated Depreciation—

Equipment ($520,000 – $400,000) ...............120,000 BRIEF EXERCISE 11-9

Inventory ....................................................................73,500

Coal Mine ..........................................................73,500 $400,000 + $100,000 + $80,000 – $160,000 = $105 per ton

4,000

700 X $105 = $73,500

BRIEF EXERCISE 11-10

(a) Asset turnover ratio:

$7,586 = 1.211 times

$6,056 + $6,474

2

(b) Profit margin on sales:

$736 = 9.70%

$7,586

(c) Rate of return on assets:

1. 1.211 X 9.70% = 11.75%

2. $736 = 11.75%

$6,056 + $6,474

2

*BRIEF EXERCISE 11-11

2012: $50,000 X 20% = $10,000 2013: $50,000 X 32% = 16,000 2014: $50,000 X 19.2% = 9,600 2015: $50,000 X 11.52% = 5,760 2016: $50,000 X 11.52% = 5,760 2017: $50,000 X 5.76% = 2,880

$50,000

SOLUTIONS TO EXERCISES

EXERCISE 11-1 (15–20 minutes)

(a) Straight-line method depreciation for each of Years 1 through 3 =

$518,000 – $50,000 = $39,000

12

(b) Sum-of-the-Years‘-Digits = 12 X 13 = 78

2

12/78 X ($518,000 – $50,000) = $72,000 depreciation Year 1

11/78 X ($518,000 – $50,000) = $66,000 depreciation Year 2

10/78 X ($518,000 – $50,000) = $60,000 depreciation Year 3

(c) Double-Declining-Balance method

depreciation rate. 100% X 2 = 16.67% 12

$518,000 X 16.67% = $86,351 depreciation Year 1 ($518,000 – $86,351) X 16.67% = $71,956 depreciation Year 2 ($518,000 – $86,351 – $71,956) X 16.67% = $59,961 depreciation Year 3

EXERCISE 11-2 (20–25 minutes)

(a) If there is any salvage value and the amount is unknown (as is the

case here), the cost would have to be determined by looking at the data for the double-declining balance method.

100% = 20%; 20% X 2 = 40%

5

Cost X 40% = $20,000

$20,000 ÷ .40 = $50,000 Cost of asset

EXERCISE 11-2 (Continued)

(b) $50,000 cost [from (a)] –$45,000 total depreciation $5,000 salvage

value.

(c) The highest charge to income for Year 1 will be yielded by the double-

declining-balance method.

(d) The highest charge to income for Year 4 will be yielded by the straight-

line method.

(e) The method that produces the highest book value at the end of Year 3

would be the method that yields the lowest accumulated depreciation at the end of Year 3, which is the straight-line method.

Computations:

St.-line = $50,000 –($9,000 + $9,000 + $9,000) = $23,000 book value, end of Year 3.

S.Y.D. = $50,000 – ($15,000 + $12,000 + $9,000) = $14,000 book value, end of Year 3.

D.D.B. = $50,000 – ($20,000 + $12,000 + $7,200) = $10,800 book value,

end of Year 3.

(f) The method that will yield the highest gain (or lowest loss) if the asset

is sold at the end of Year 3 is the method which will yield the lowest book value at the end of Year 3, which is the double-declining balance method in this case.

EXERCISE 11-3 (15–20 minutes)

(a) 20 (20 + 1) = 210

2

3/4 X 20/210 X ($774,000 – $60,000) = $51,000 for 2012

1/4 X 20/210 X ($774,000 – $60,000) = $17,000

+ 3/4 X 19/210 X ($774,000 – $60,000) = 48,450

$65,450 for 2013

EXERCISE 11-3 (Continued)

(b) 100% = 5%; 5% X 2 = 10%

20

3/4 X 10% X $774,000 = $58,050 for 2012

10% X ($774,000 – $58,050) = $71,595 for 2013

EXERCISE 11-4 (15–25 minutes)

(a) $279,000 – $15,000 = $264,000; $264,000 ÷ 10 yrs. = $26,400

(b) $264,000 ÷ 240,000 units = $1.10; 25,500 units X $1.10 = $28,050

(c) $264,000 ÷ 25,000 hours = $10.56 per hr.; 2,650 hrs. X $10.56 = $27,984

(d) 10 + 9 + 8 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 55 OR n(n + 1) = 10(11) = 55

2 2

10 X $264,000 X 1/3 =

$16,000

55

9 X $264,000 X 2/3 =

28,800

55

Total for 2013 $44,800

(e) $279,000 X 20% X 1/3 = $18,600

[$279,000 – ($279,000 X 20%)] X 20% X 2/3 = 29,760

Total for 2013 $48,360

[May also be computed as 20% of ($279,000 – 2/3 of 20% of $279,000)]